The recent report by IPCC, the UN’s panel for climate change was nothing less than “code red for humanity”, according to Secretary-General António Guterres. Time’s running out on billions of people and extreme ecosystem changes are bound for the upcoming decades. Recent floods and wildfires in Europe brought the effects to our doorstep. The willingness to act is higher than ever. So what’s currently missing and what’s the leverage of the innovation and product development community?

Stuck in reverse

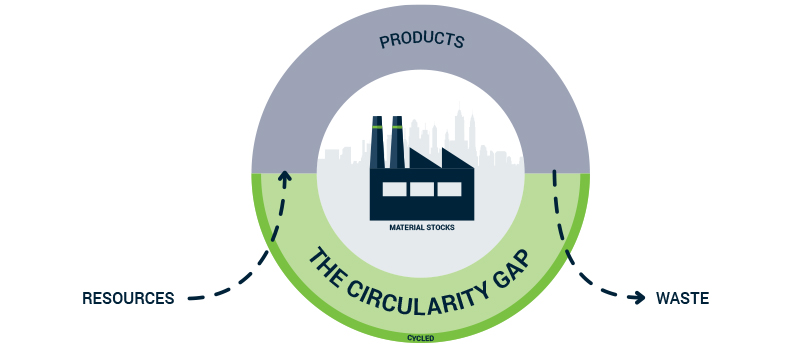

Despite all efforts by circular economy pioneers and (modest) policy actions, we’re swimming against the current. Earth Overshoot Day falls earlier each year. The Circle Economy calculated that our world is only 9% circular and the trend is negative (The Circularity Gap Report, 2019). Average welfare and income is rising, sparking less sustainable consumption patterns (e.g. increased meat consumption; Our World in Data, 2019). ING researched that countries with a higher GDP per capita tend to reuse less (ING Economics Department, 2020).

Conceptual representation of global resource stocks & flows (adapted from The Circle Economy) © VERHAERT

Conceptual representation of global resource stocks & flows (adapted from The Circle Economy) © VERHAERT

So there you are. An individual, SME or corporate with good intentions, facing the harsh reality. The global engine is stuck in reverse. The market isn’t going to self-regulate. Consumers want change, but they don’t want to pay for it. You want to include environmental valuation into your pricing, but fear to become a niche product for the lucky/crazy few. So you decide to wait for your neighbor to act or for the government to force you. The circular paradox is paralyzing. Or is it?

Why are we failing?

Circular economy (CE) is widely viewed as the solution for many sustainability issues, such as climate change. Nevertheless, CE faces various negative effects that need to be overcome to become successful.

| Circular economy challenges | Potential leverages for designers | |

| 1. No true pricing | Negative environmental effects of market activities (external costs), such as climate change and air pollution, aren’t reflected in prices. |

|

| 2. Increased cost model | Transaction and operational costs are higher in a CE, partly explained by the higher labor intensity of reuse and recycling strategies. |

|

| 3. Too low volumes (demand and/or supply) | For secondary goods and materials prevent circular markets from coming about. |

|

| 4. Reluctant investors | The innovative nature of circular economy makes investing in CE riskier than conventional businesses. Furthermore, financial institutions overlook ‘linear risks’ such as stranded assets risks and risks of more stringent environmental laws. |

|

| 5. Mindset change required | Consumers act in manners of convenience and habit. CE initiatives imposes disruptions that create friction and therefore slower adoption rates. Imagine our well-earned comfort of owning a car rather than sharing one. |

|

| 6. Risky business models | Product-as-a-Service business (PaaS) model, one of the main circular business models, is perceived to be riskier than conventional businesses (e.g. higher usage risks, limited collateral risks, higher credit risks and higher moral hazard risks) (ING, Rethinking the road to circular economy, 2020). |

|

Furthermore, we need to ask ourselves whether we’re focusing on the right actions. Our world can’t afford for circular economy to be mere greenwashing and window-dressing. The plastic straw ban caused a lot of backfire for policymakers as it may confer a ‘moral license’ as if consumers will feel they have done their part. According to NatGeo plastic straws comprise merely 0,025% of ocean plastic. Many companies are inclined to focus on visible efforts (e.g. in consumer packaging) rather than supply chain or energy management innovations. In our economic reality, realizations will only happen when a win-win situation is achieved. Which brings us to solution thinking.

Circular economy needs a business case

Let’s start off with the biggest reason why circular economy innovations tend to fail. The current linear model is simply more profitable. In the absence of true pricing and governmental incentives (see further) a product-centric business case is often doomed to fail due to the elements described in the previous chapter.

A potential bypass for this viability trap is to go back to the basics of sweet spot thinking: maintain a positive balance between value and costs. CE-innovations also need to bring meaningful added value to the customer. Start from job-to-be-done thinking and consider new business models to create new value. Dare to disrupt, as incremental changes might not positively balance the scales of new cost vs. new value.

Download the perspective to continue reading about circular economy and business cases, behavioral economics, partnerships, true pricing & policy incentives

Authors: Stijn Smet & Filiep Dewitte